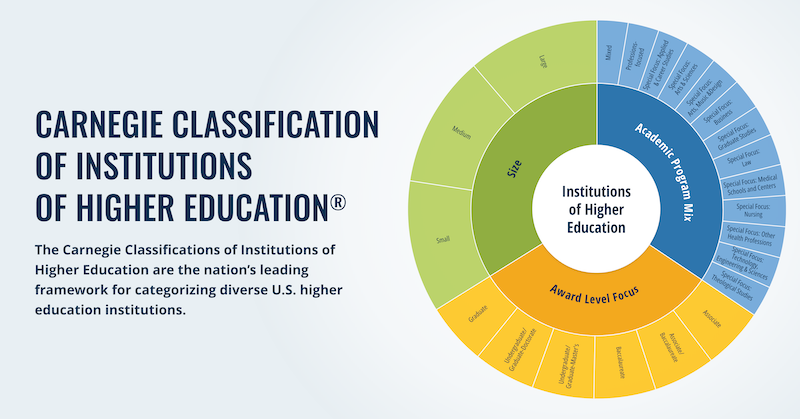

Editor’s note: This is the second of three blog posts based on a series of articles produced by the Brookings Institution that make recommendations for an appropriate federal role in education policy. Today, we highlight a memo aimed at improving high school and college graduation rates, co-authored by Kelli Parmley and Marshall (Mike) S. Smith of the Carnegie Foundation.

Economic growth following the financial crisis of 2008 contained a lopsided recovery that illuminated the critical need for more college graduates in the United States. Of the 11.6 million new jobs, 95 percent required a degree or other postsecondary training, according to the Center for Education and the Workforce at Georgetown University. Most of the jobs held by workers with a high school diploma or less that disappeared did not return.

Continued economic growth will be stunted unless the nation steps up efforts to increase high school graduation rates and ensures that those students are prepared to be successful in college. Within three years, more than two-thirds of all jobs will require at least some higher education, but the Center at Georgetown warns that, at the current rate, the nation is facing a shortfall of 20 million degrees.

High school and college graduation rates are increasing, but not by enough, especially for low-income, Hispanic, and African American students. While the high school graduation rate for white students is 88 percent, it’s only 73 percent for black students and 75 percent for Hispanic students. The inequity deepens at the college level, where, according to the U.S. Department of Education’s Digest of Education Statistics, about 57 percent of Asians and 40 percent of whites hold a bachelor’s degree or higher, making them about twice as likely to earn college degrees as African American and Hispanic students.

Yet, there are strategies that work to improve these outcomes, note Kelli Parmley and Marshall (Mike) S. Smith in their report, Improving and equalizing high school and college graduation rates for all students. It’s part of a series by the Brookings Institution of 12 Memos to the President on the Future of Education Policy.

Where are the leaks in the college graduation pipeline?

Parmley and Smith identify three “critical junctures,” or leaks, in the graduation pipeline where students are most at risk for dropping out or ending their formal education. The impact of the opportunity gap on education equity is an underlying factor at each point.

- High school graduation: After being stuck for decades, the national high school graduation rate reached 82.3 percent in 2014. However, there is still a way to go to reach the 90 percent goal by 2020, set by GradNation, an alliance of education and civic organizations. Although black and Hispanic students are primarily responsible for the increase, they still fall 15 to 17 percentage points below white students in high school graduation rates.

- Pre-college remediation (non-credit developmental math and English classes in college): Every year, nearly 60 percent of incoming community college students aren’t prepared for college-level math and are referred to a non-credit bearing developmental mathematics class. Only 20 percent of these students go on to earn college math credit within three years. Black and Hispanic students are significantly more likely than white students to wind up in developmental math.

- College graduation: Between 2004 and 2014, graduation rates fell slightly at community colleges, to less than 30 percent, and increased a bit at four-year colleges, to just under 60 percent. Hispanic students have bucked the trend at community colleges and are improving at a faster rate than white and black students. But at four-year colleges, black and Hispanic students lag behind white classmates by 22 and 10 percentage points respectively.

“The exciting story is that we know how to substantially plug the leaky pipeline to increase secondary school graduation rates, improve outcomes in developmental courses, and boost college graduation rates.”

We have the know-how

“The exciting story is that we know how to substantially plug the leaky pipeline to increase secondary school graduation rates, improve outcomes in developmental courses, and boost college graduation rates,” they write. “Moreover, we have robust examples of successful interventions at each of the three main links in the pipeline.”

The high schools and colleges that have successfully tackled these issues did so using the principles of continuous improvement. Instead of throwing a variety of single interventions at the problem to see if any stick, they took time to understand the processes and actions in their systems that created the problem, researched evidence-based strategies, adapted those strategies to their context, conducted rapid testing of interventions and adjusted them if necessary, and used data throughout the process as a guide.

Fresno Unified School District in California’s Central Valley, with over 80 percent free and reduced lunch and over 75 percent Hispanic and African American students, used the continuous improvement approach to create a data system that notifies a student’s counselor if the student is off track for graduation or college preparation due to such factors as excessive absences, low test scores, or not being enrolled in college preparatory classes. Graduation rates rose from 70 to 84 percent from 2010 to 2016, more than double the national gains.

Getting students into college is just the first step; preparing them to be successful has been more difficult. In its latest report on the issue, the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center found a decline in graduation rates between students who started college in the fall of 2009 — both in four-year and two-year colleges — from the cohort that entered in the fall of 2008. The actual number of graduates increased because the Fall 2009 cohort was larger than the previous year, but, by the same token, the number of students who left college without a degree or certification also rose.

A key contributor to these lower completion levels is the dismal success rate in developmental (also known as remedial) courses. As noted above, 80 percent of students enrolled in these pre-college credit classes don’t pass them and, therefore, are locked out of their college, advanced credentialing, and related career goals.

In recent years, however, different organizations and colleges have created alternative developmental education courses to address the problem. One of the most successful is Carnegie Math Pathways, which followed the principles of improvement science — such as seeing the problem as system wide, learning what students said was not working, and conducting ongoing measurement of interventions to quickly determine if they’re helping students and change the if they’re not — to redesign developmental math. With five years of implementation behind it, students in the Pathways courses have triple the success rate in half the time as students in traditional developmental math classes.

Both Georgia State and Florida State Universities used data in a similar manner to Fresno Unified to track student progress and intervene when students were off course. Georgia State increased graduation rates from 32 percent to 54 percent between 2003 and 2014, while Florida State’s rate jumped from 63.2 percent in 1988 to 79.1 percent for the freshmen class of 2008. Black students at FSU pulled nearly even and Hispanic students slightly exceeded the overall rate.

“All of these examples can be replicated,” write Parmley and Smith, by using continuous improvement methodology to adapt them at other colleges. The federal government can provide an assist through these five recommendations:

- Set clear national goals for college graduation and encourage states to do the same, and see college graduation as part of a continuum that begins in high school by ensuring that students are on track and taking the classes that colleges require.

- Add a new title to the upcoming reauthorization of the Higher Education Act that provides resources for colleges to implement robust data systems.

- Partner with existing organizations engaged in this work to establish clear goals for high school graduation within four years and six years.

- Support legislation to improve existing K-12 state data systems so school counselors can intervene quickly when a student needs support.

- Use existing resources, such as federal education labs, to conduct research and development that provides more evidence of successful interventions.

Colleges and school districts that have used continuous improvement to increase graduation rates, especially as a means of closing the graduation gaps based on race, ethnicity, and income, often do so locally, without federal or even state assistance. But that’s too heavy a lift for most places, in particular small districts and colleges that don’t have the financial or human capital to spare. Federal support, therefore, is crucial in scaling these proven interventions, note Parmley and Smith. Otherwise, it’s unlikely that colleges and high schools on their own will be able to close the 20 million shortfall in college degrees and postsecondary training that’s essential for the nation’s continued economic health.

December 16, 2016

A new president, a new secretary of education, and a new version of ESSA are creating a confluence of unknowns about the future federal role in education policy. Carnegie Foundation scholars propose their recommendations as part of a series of Memos to the President.

January 5, 2017

Failure can be a learning experience, but only under certain conditions. The work must matter, and there has to be a leader who can manage the costs of failure, understands improvement research, and keeps people focused on finding a solution instead of placing blame.