In 2011-2012, nearly a quarter of the teachers in the U.S. had five or fewer years of experience and nearly 7 percent were brand new to the profession.[1] While novice teachers bring new skills, perspectives, and energy to their schools, they also tend to leave the profession at high rates, with nearly half leaving the classroom in their first five years.[2],[3]

At a recent event hosted by Carnegie’s Washington, D.C., office, this statistic was brought to life as three beginning teachers reflected on their futures in the classroom: one was committed to staying, one was committed to leaving, and the third was looking beyond the classroom to an administrative role where he hoped he might “have an even bigger impact” on students’ lives.

Invited to respond to “Beginners in the Classroom,” a report on the condition of beginning teachers by Carnegie Senior Associate Susan Headden, these teachers spoke candidly about their experiences as novice teachers. And though the contexts in which they entered the teaching profession differed—Lauren Phillips cut her teeth as a New York City Teaching Fellow, Rene Rodriguez as a Capital Teaching Resident in Washington, D.C., and Diana Chao as a university-trained teacher in Montgomery County, Md.—all three agreed that their first year might have been improved by more frequent and more actionable feedback from the instructional leaders at their schools.

Teachers who felt engaged in their schools and were made to feel confident about their classroom contributions were significantly more likely to stay at their schools.

Research suggests feedback might do more than simply improve teachers’ early experiences and performance in the classroom; it might help convince them to stay, too. In a 2012 study by TNTP, top-performing teachers who experienced supportive, critical feedback and recognition from school leadership stayed in their schools for up to six years longer than top-performers who did not receive such attention.[4]

Likewise, in a survey of 580 teachers in the Baltimore City Public School system, researchers from Carnegie’s Building a Teaching Effectiveness Network (BTEN) found that teachers who felt engaged in their schools and were made to feel confident about their classroom contributions were significantly more likely to stay at their schools. Among the 25 percent who felt least confident and least engaged in their school communities, fewer than half were likely to stay the following year.

Despite growing evidence that high-quality feedback—feedback that builds trust and leads to improvements in teaching and learning—may be a crucial lever for increasing teaching quality and retention rates, providing such feedback has proven a significant challenge in America’s school systems. Even in districts that have made instructional improvement a priority, the feedback teachers receive is often infrequent, inactionable, and incoherent.

Even in districts that have made instructional improvement a priority, the feedback teachers receive is often infrequent, inactionable, and incoherent.

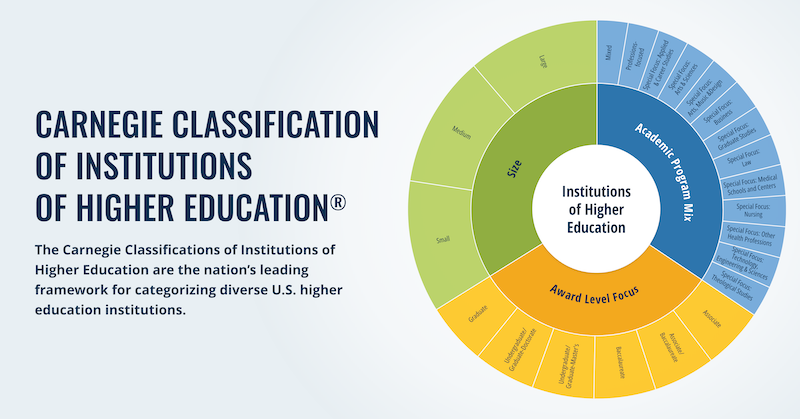

Carnegie addresses this challenge in its latest publication, Developing an Effective Feedback System, which aims to help districts rethink feedback not simply as a series of isolated conversations between principals and teachers, but rather as a complex system of many interconnected factors at the district, school, and classroom level—all of which shape the nature of feedback teachers receive.

Drawing on scholarly research and in-depth interviews with expert practitioners, the report provides a framework of key drivers—processes, norms, and structures—that should be in place at each level for a district to maintain a coherent, high-quality feedback system that can drive improvement in teaching quality and contribute to the retention of teachers who are successful. A clear instructional framework, training and support for feedback providers, coherent and coordinated feedback, and a trusting culture committed to continuous learning are among the key drivers explored in greater depth.

To provide even greater direction for school-based educators working with new teachers, the paper also outlines components of a model feedback process, including concrete steps principals and coaches can take to coordinate and improve the interactions they have before, during, and after feedback conversations with novice teachers. These are conversations that, according to the panelists on Carnegie’s recent panel, tend to lack substance, if they occur at all. And they are conversations that, if done well, have the potential to improve new teachers’ practice and, hopefully, keep them in the classroom for the long haul.

[2] Matthew Ronfeldt, Susanna Loeb, and James Wyckoff, “How Teacher Turnover Harms Student Achievement,” American Educational Research Journal 50, no. 1 (2013): 4–36. Retrieved from: http://aer.sagepub.com/content/50/1/4.

[3] Richard Ingersoll and Lisa Merrill. Seven Trends: The Transformation of the Teaching Force. Consortium for Education Policy Research. (2013) Retrieved from: http://www.cpre.org/sites/default/files/workingpapers/1506_7trendsapril2014.pdf.

March 25, 2014

Dan Heath, author of Switch: How to Change Things When Change is Hard, at Carnegie’s Summit on Improvement in Education, presents an approach for working towards change in education.

May 2, 2014

Design-based implementation research (DBIR) bears a family resemblance to a portion of the work done by Networked Improvement Communities (NICs). But NICs are not a research approach, and their raison d'être is not theory building.