Trained teacher evaluators in Tennessee conducted more than 295,000 classroom observations of the state’s 64,000 teachers during the 2011-12 school year. That’s a lot of hours, especially when you factor in the time administrators spend scheduling, planning, and debriefing each observation. Many principals complained they did not have enough time to complete the state’s new multi-step evaluations.

In a 2012 report from the Tennessee Department of Education, the state’s educators reported that “the amount of time spent to implement TEAM [the new system] was unimaginable.” Even among those for whom time was not an issue, many felt the hours had not been well spent, as they lacked the instructional expertise to provide meaningful feedback, especially to struggling teachers most in need of improvement.

The evaluation systems also allocated resources inefficiently, treating all teachers with the same intensity.

Educators in Tennessee were not alone in voicing their frustration about the evaluation process. Reports from Los Angeles, the District of Columbia, Rhode Island, and elsewhere confirm that many systems placed significant burdens on states’ and districts’ resources. In addition to being expensive and time consuming, the evaluation systems also allocated resources inefficiently, treating all teachers with the same intensity, even after results showed significant variations in teachers’ skills and needs.

Seeking policies that bring greater quality and efficiency to their evaluation systems, many states and districts have begun to tinker with their original blueprints (or adjust their first drafts). One emerging strategy has been to replace the one-size-fits-all approach with one that evaluates teachers differently based on their prior performance results. Using data from previous evaluations, districts can make informed decisions about which teachers require more or less attention in subsequent evaluation cycles.

Though districts approach evaluation differently based on their goals and resources, three major trends have emerged as differentiation has become an increasingly popular option.

Varying the Frequency or Format of Evaluation

While most teachers in Delaware and Ohio receive annual performance evaluations, policies in both states allow districts to evaluate top-performing teachers biennially. (In Delaware, highly effective teachers are observed annually, but they receive full summative evaluations only every other year.)

Similarly, in Burlington, Vt., and Pittsburgh, Pa., high-performing teachers can opt to pursue action-research, self-directed study, or collaborative projects with other top-performers in lieu of traditional evaluation. Teachers receive annual summative evaluations for their progress in these projects, but the process is generally less resource intensive for school administrators, who draw heavily on evidence from teachers’ self-reflections and peers’ observations to determine teachers’ ratings.

Varying the Frequency or Format of Classroom Observation

Even in districts that rate all teachers annually, officials now vary how often they observe teachers based on teachers’ past evaluations. In response to educators’ request for policies that allowed them to “spend more time with the teachers most in need of improvement, while reducing the amount of time spent with teachers whose student outcomes demonstrate strong performance,” the State Department of Education in Tennessee recently introduced a differentiated approach, varying observation frequency according to teachers’ licensure status and past performance. Top-performing veterans are formally observed only once, while novice teachers and struggling veterans participate in at least four observations annually.

Meanwhile, teachers in Hillsborough County, Fla., undergo anywhere from three to 11 classroom observations, depending on their past performance. While many of these observations are formal visits lasting 30 to 60 minutes, others are shorter and more informal, often focused on a particular skill or practice rather than on the entire instructional framework (as in a formal observation). By combining these and other formats—walkthroughs, check-ins, etc.—observers can differentiate the length and type of time they spend in teachers’ classrooms, providing more or less feedback as needed.

Two sets of eyes are better than one when it comes to evaluating teachers’ practice

Multiple Evaluators

As the MET project recently confirmed, two sets of eyes are better than one when it comes to evaluating teachers’ practice. Fortunately, peer evaluators are becoming an increasingly popular way to distribute responsibility and expertise for classroom observations. Many systems now employ different types of observers—peer observers, instructional coaches, mentor teachers, etc.—for teachers with different needs. Teachers in Maricopa County, Ariz., undergo four observations annually, but administrators can decide how many of these they conduct and how many they delegate to trained peer evaluators. Drawing on what they know about teachers’ past performance and their own instructional strengths, principals and coaches can work together to create differentiated combinations of supervision and support.

Several districts combine these strategies, creating systems that are highly-responsive to teachers’ evaluation results. Others use just one, differentiating only slightly. In either case, it’s too early to tell if differentiation has dramatically improved systems’ efficiency, but anecdotal evidence is encouraging: Even in districts where differentiation has definitely not reduced costs or administrators’ workloads—and there are certainly some—officials believe differentiation has allowed them to achieve greater quality by ensuring resources are invested where they’re needed most.

For more information, download Evaluating Teachers More Strategically: Using Performance Results to Streamline Evaluation Systems.

———–

The research for this post was conducted under Carnegie’s Advancing Teaching – Improving Learning program.

May 28, 2013

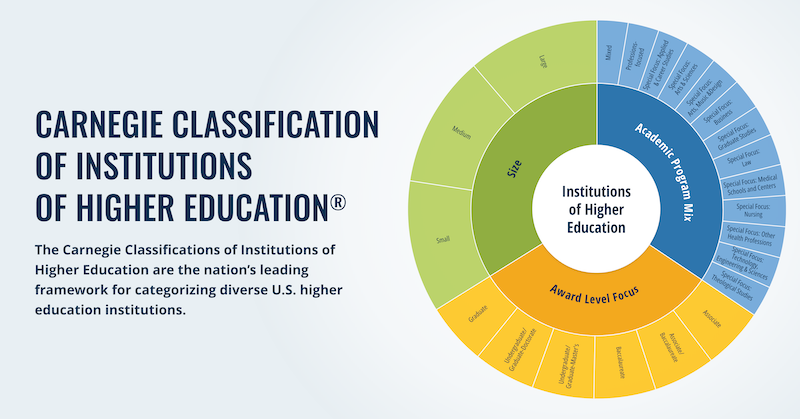

The current use of the Carnegie Unit was never the intent when it was first created. The Carnegie Foundation is embarking on an initiative to revisit the Carnegie Unit.

June 11, 2013

White paper, Improvement Research Carried Out Through Networked Communities: Accelerating Learning about Practices that Support More Productive Student Mindsets, explores improvement science as a way to address problems facing educators.