The Carnegie Foundation’s fourth annual Summit on Improvement in Education is March 27-29, 2017. Over the course of three days, teachers, school and district leaders, researchers, foundations, and innovators will discuss their successes and challenges, and offer tools and tips related to effective school change. This is the second post in a series discussing key insights and reflections from Summit presentations.

Empathy tends to be undervalued when education reform is afoot. Teachers and students generally feel that change is done to them, rather than something they participate in, even when it comes to the simplest courtesy of being asked for their opinions. As years of frustration over unsuccessful policies in education and elsewhere can attest, top-down mandates are not a promising means of engendering trust and receptivity and, therefore, are not especially effective at driving deep, enduring change.

Yet, seeking input alone isn’t enough. A district superintendent, for example, needs to know the right questions to ask school principals to try to understand what’s behind, say, low-reading levels; principals have to determine why teachers are struggling with some students; and teachers have to know what’s going on with their students — in their heads, in class, and outside of school. A process called journey mapping is increasingly being used by educators to hone in on two fundamental principles of improvement science: seeing the system that’s producing the problematic outcomes, and being user-centered, which means becoming aware of students’ (or teachers’) perspectives and their experiences, feelings, and needs.

“The whole issue in education is if you want to teach someone well, you have to know who you’re teaching,” said Sharon Greenberg, literacy lead for the Tennessee Early Literacy Network, a networked improvement community (NIC) created jointly in 2016 by the Tennessee Department of Education and the Carnegie Foundation. Greenberg wrote the journey map questions, designed the protocols, and organized the analysis — all topics she and her colleagues from Carnegie and Tennessee will be discussing in detail during a session at Carnegie’s 2017 Summit on Improvement in Education.

If you want to teach someone well, you have to know who you’re teaching.

Seeing the System and the Student

The student journey mapping that was done in Tennessee had several parts. Because the NIC’s aim is to improve early literacy, district leads were asked to identify a struggling third grade student and start by reviewing that child’s file back to the start of their formal schooling. They then did short interviews with each of the child’s teachers to create a chronology of the child’s academic progress, behavior, and interventions over the years, as well as any additional circumstances that might have impacted the child’s well-being, such as homelessness; the death, illness, or disability of a parent; and drug or alcohol abuse in the home. Following this background work, the teacher had a brief conversation with the child. Prompts were straightforward and aimed at understanding the child’s experience of learning to read and write. They included questions like: Do you like to read? Can you tell me about the last thing you read that you really liked? Can you remember learning to read when you were little — before you even started school? Once the interviews were done, district leads were asked to write up their journey maps, add a written reflection, and post their maps on the Tennessee Early Literacy Network (TELN) blog.

During a convening that took place shortly after the maps had been posted, Greenberg and her colleagues helped NIC members examine the journey maps to look for common patterns and trends across all of their schools, an exercise that many described as “eye-opening.”

“Two things occurred to me when I looked at it,” said Margaret Bright, a literacy specialist and a network district lead from Lenoir City Schools, about 30 miles southwest of Knoxville. “One was, I [always] knew the problem was big, I didn’t realize it was this big.” The other thing, she added with a laugh was, “Oh, thank goodness we’re not the only district.”

It is a relief and a comfort to know that other districts are affected by the same problems because it helps “them to see problems systemically rather than personally, and it builds community and trust among people,” explained Greenberg.

Among the most prevalent problems that transcended district boundaries was poor communication among teachers and intervention specialists which often resulted in kids “bouncing in and out of intervention,” or not having any alignment in instruction or expectations between the classroom teacher and interventionist, said Amanda Tinker, also a Lenoir district lead and the assistant principal at Lenoir City Elementary School.

This made data meetings frustrating and ineffective, added Tinker, who will be on the panel with Greenberg at the Carnegie summit. Without everyone being on the same page, meetings often turned into problem-sharing sessions rather than leading to specific actions to take to help struggling students. That has all started to change. The NIC is focused on improving communication and coordination among all teachers, including physical education, and support services. In some schools, intervention and classroom teachers now have “huddles” to discuss and coordinate strategies for students, and schools have shared Google documents where teachers can add information about a student that they’d like to discuss at the next meeting.

It can be a sobering lesson when the journey maps uncover places where interventions weren’t working for students or point to missed opportunities when interventions might have worked, but nobody did anything. For example, one student journey map indicated a history of difficulty staying focused on his work and being disruptive and impulsive during class. The parents refused to have him tested for attention deficit disorder and wouldn’t consider medication.

In the reflections portion of the journey map, this child’s current teacher described being troubled by “the seemingly ongoing battle between teacher and parents regarding the student’s difficulty with attention and focus,” and wondered if it’s possible “the school did not do enough to meet his needs.” The boy was held back a year, but the problems persisted, prompting the teacher to add, “I also am still struggling with how to help students such as this one.”

Ginger Leach, one of the two regional directors in the Tennessee NIC, told a story of how one teacher learned through her student interview that the reason a student wasn’t reading at home was because there were no books in the house and the parents never took the child to the library. “Now, that teacher makes sure the child has a book to take home,” said Leach, which may have an additional motivational benefit, because it tells the child “that someone is willing to go that extra mile for me.”

In addition to the student journey maps, district leads in TELN were asked to do a teacher journey map focused on learning about teachers’ experience teaching reading. They found that many of their colleagues felt unprepared to teach reading. Before doing that mapping, district and school leaders probably would have said that just a few of their teachers didn’t know how to teach reading, said Leach, but “the journey mapping helped them see that it’s a larger scale problem than it seemed.”

It’s not just a Tennessee problem; a 2010 study by the National Council on Teacher Quality found that 75 percent of pre-service programs for elementary school teachers did not teach methods of reading instruction. A priority of the state commissioner in Tennessee is to improve both the preparation of pre-service teachers and support for those in the classroom.

The Tennessee Early Literacy Network is just a year old, so it’s too soon to have any results on how it’s working for students. But district leads say they’re definitely seeing changes among teachers. Bright noticed the difference right away in Lenoir City Elementary School when she asked two teachers if they’d like to do some improvement work. She was nervous and expected pushback because she knows they’re already busy, but found the opposite reaction. “They were thrilled; they were excited,” and they started suggesting other improvements. She credits journey mapping with helping to open channels of communication and collaboration between teachers and school leaders. “[Teachers] are the experts in the building. Those are the experts in our district, and if we don’t empower them and get them to help start making these changes, the changes aren’t going to happen. It gives them a voice that they didn’t feel they had before.”

February 8, 2017

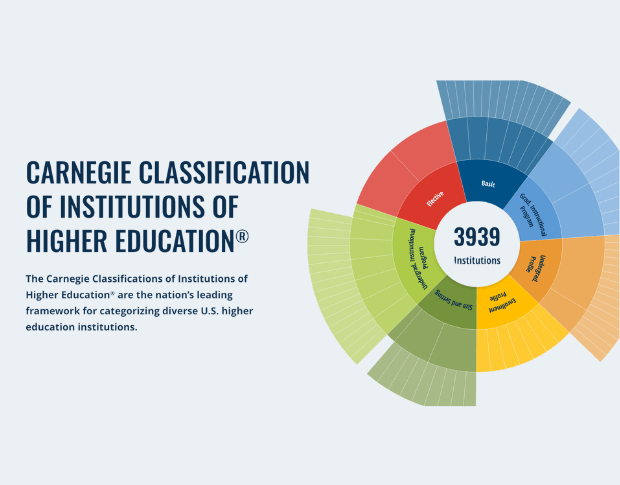

User-centered design is key to developing meaningful change to improve student achievement, and networked improvement communities help ensure and maintain the focus on human needs.

February 23, 2017

A special issue of the journal Quality Assurance in Education breaks down seven approaches to improvement in education, beginning with the networked improvement model. Explore key features and principles of this method through a successful example of helping new teachers.