Scaling Real-World Learning: How Kansas City is Preparing Students for the Future

Delve into this thoughtful Q&A with Dr. Bill Nicely, Educator-in-Residence for Real World Learning at the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation. In this conversation, Bill delves into the Real World Learning initiative, sharing the initiative’s origins, goals, and the remarkable impact of Market Value Assets on students in the Kansas City region. He reflects on the Collaborative’s efforts to help high school students in the region graduate with immersive, profession-based learning experiences and skills.

Bill has 32 years of service in public education, including 11 years as Kearney School District (KSD) superintendent and five years as a small school superintendent in Leeton, Missouri. He is a former high school principal and assistant principal at Sedalia Smith-Cotton High School and began his career in education teaching high school chemistry and physics in Louisburg, Kansas.

Tell us a bit about the Real World Learning Initiative supported by the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation Kauffman Foundation. What are you hoping to achieve?

The Real World Learning Initiative (RWL)is a Kansas City area collaborative that operates with support from the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation to prepare the Kansas City region, students, and employers for the future. The Initiative includes 34 school districts, ranging from as small as 350 students to as large as 25,000. These districts are located across the urban core, which includes primarily students of color and an increasing immigrant population, to suburban areas, and even rural outskirts. Diverse districts are working together with a common goal, aiming to impact all high school students—just under 100,000 students in total. The shared goal is for every high school student to graduate with a standard diploma and a deep, immersive learning experience that is profession-based.

To be clear, it’s the school districts, business and community partners, and parents that really drive this work. However, the Foundation provides critical support to the collaborative by providing resources, listening to community members, gathering feedback, and reflecting and reporting back on findings and research.

What is Real World Learning’s origin story and how has the initiative evolved?

The Real World Learning initiative began in 2018. At the time, I was a public school superintendent at one of the first six participating districts that make up Northland CAPS, part of the CAPS Network. My colleague at the Kauffman Foundation, Donna McDaniel, posed a critical question: We know profession-based experiences, like Center for Advanced Professional Studies (CAPS) programs and tech centers, are life-changing for students. But if they’re good for some students, can they be good for all students? The answer was an emphatic “Yes.” We then asked ourselves, how can we create opportunities for all students to have these experiences? What would that mean for public education? With support from the Kauffman Foundation, the Real World Learning Collaborative was born.

Originally, we thought four to six school districts would be participating in the initiative. As it turned out, 16 districts and charter schools accepted the challenge. That alone is a testament to the value of these deep, immersive experiences for our students. The Foundation provided individual grants to districts to develop plans and move forward in this direction. It really all started with a collective vision—our “Portrait of a Graduate,” which still exists today. In 2022, we followed up with an RWL collaborative strategic plan, and we continue to review our thinking through strategic refreshes.

Interestingly, many agree that the pandemic actually contributed to the cooperation and teamwork within our RWL Collaborative. We began meeting virtually and connecting personally about our struggles and to strategize around what was best for kids. We realized that regardless of whether members were from a charter school, a large affluent suburban district, or an urban core school each facing different challenges, we were able to help each other navigate those challenges and provide support.

The Real World Learning website highlights your ambitious aim of ensuring all students in the Kansas City region graduate with one or more Market Value Assets by 2030. Can you explain what these Market Value Assets are and why Real World Learning is so focused on them?

We refer to the learning experiences that help students build resilience and prepare them for success beyond high school as Market-Value Assets (MVAs). These experiences come in four categories:

- Work-based experiences, including internships and client-connected projects with industry, non-profit, and civic organization partners, where small groups of students work with their teacher and a partner client on real-world problems.

- Entrepreneurial experiences, where students generate ideas and work with outside adult experts.

- Industry-recognized credentials, including apprenticeships and other certifications.

- College credit. Nine or more hours (or three courses) in a pathway relevant to their future studies.

We believe these experiences can be especially profound for historically marginalized students, typically from low socioeconomic backgrounds and often students of color. This is because students forge relationships with professional adults and learn what life is like in a professional setting, which helps them envision their futures. In fact, we have learned that students who graduate high school with an MVA are more likely to pursue further education and successfully navigate the journey to employment. Early on in this work, we asked students and teachers what changes they saw in themselves or their students after gaining high-quality Market Value Assets. We created a list of attributes, or “outgrowths,” as we call them. You might recognize these as social, professional, or durable skills. Some examples in our guide for schools and districts include benefiting from social capital, seeking feedback from mentors outside of school, planning and managing projects, being proactive, differentiating contexts, and collaborating to achieve an end goal. “Collaborating to an end” is one of my favorites because it’s not just about working together—it’s about getting the job done.

These MVA experiences lead students to develop, mature, and gain these outgrowths. They grow into them, which is where the name came from. As a result, students are different. Their brains have been rewired, and they’ve experienced real progress. Unlike a concept such as the quadratic equation, this skill set is something that students will possess and carry with them for the rest of their lives. Being able to work through difficulties, collaborate to an end, research, refine plans, and interact with adults in a professional setting are all critical skills that will benefit them well into the future.

To quote my colleague Dan Tesfay, Director of Research, Learning, and Evaluation Initiatives at the Kauffman Foundation, these MVAs are “ridiculously elegant.” These experiences transcend school districts, organizations, and business settings. Each district tackles them differently, deciding which ones to prioritize and how to remove barriers for students. Yet, the outcomes are the same for students. They all experience outgrowths. As one school leader said, “MVAs are the ‘what’ and outgrowths are the ‘why.'”

How are you supporting educators in this work to actualize your ambitious vision?

One example is our initiative to offer paid professional development to teachers over the summer to support their integration of client-connected projects into core content areas in the classroom. During the sessions, we review the components of client-connected projects—the most popular student learning experience—and focus on how to find business partners, strategies for working with students to develop projects, and so on. We just finished the second year of this summertime teacher professional development program and doubled the number of participants from the first year—from 61 to 125 educators.

Also, we assembled mentor teachers to facilitate the summer professional development and then followed up with these teachers during the school year to assist and support them in implementing client-connected projects in the classroom. The goal of this work is to provide teachers with tools and strategies to problem-solve and refine their methods with peer guidance.

We developed a survey with the Urban Education Research Center at the University of Missouri-Kansas City to measure the impact of student growth (exhibited by outgrowths) and teacher mindsets. The results have been incredible. Overwhelmingly, teachers reported feeling more comfortable integrating client-connected projects into core content standards. For example, teachers are sitting down with students and saying, “Here’s your project, and here are the learning standards I need to see you master this semester. Which of these standards aligns with your project?” By doing this, we believe students will perform better on assessments and content standards as well as develop key Market Value Assets.

What results have you seen from the implementation of this work in schools and districts, and how have these outcomes inspired community members in the region?

I am thrilled to share that 52% of all recent high school graduates earned an MVA before graduation, based on data from the previous school year compiled by our independent research consultant, MDRC. This is a significant number of students who are graduating high school prepared for their futures with real-world, profession-based experiences and skills.

Additionally, I’ve heard local business leaders casually drop the term “market value asset” and name how important these experiences are for students in various meetings. Brian Crouse, from the Missouri Chamber of Commerce, told me recently that he no longer hears the business community complaining that our kids “can’t do this or that” or “don’t know how to do math.” That criticism has faded because students, having acquired MVAs, are behaving differently, and businesses are interacting more deeply with schools.

What are you learning from this collaborative about the potential of schools to be more fully integrated into their communities?

We are learning that while challenges differ by district based on size and other factors, we often see cross-collegiality in finding similarities in their problem-solving strategies. And what’s really interesting is that you would think the Cohort 1 school districts would be the most advanced and farthest along. But that’s not always the case. Some of the Cohort 2 and 3 school districts are actually quite far advanced because they’ve learned from the others before them.

While we see variation by district, promising strategies and outcomes are present across the region to ensure students acquire MVAs. For instance, some districts focus exclusively on client-connected projects and internships, while others offer opportunities for students to obtain industry-recognized credentials (IRCs). Regardless of their approach, the increase of students earning at least one MVA creates a new kind of school community where the majority of students are solving real-world problems, teachers are teaching in new ways, and community members and industry partners are also benefiting more from a new market of potential future employees. Overall, it’s a tremendous opportunity for all involved.

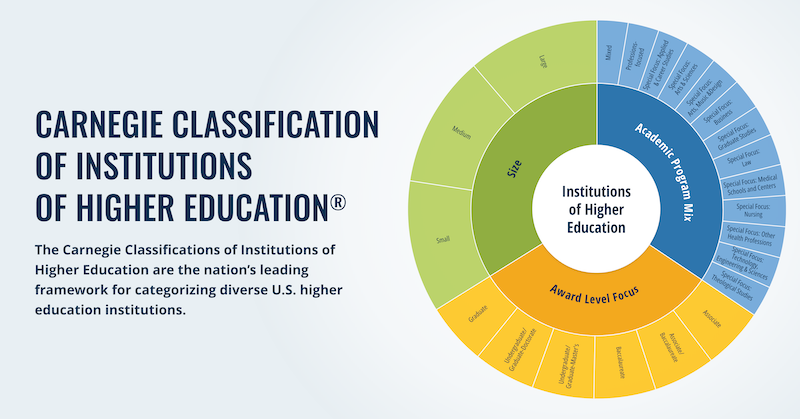

Carnegie’s north star is focused on social and economic mobility for all students. When you think about business partnerships, are you focusing on local community partners, or are you tapping into national networks, especially with the prominence of remote work and learning?

The short answer is that the vast majority of these experiences are local. We’ve learned that it’s important to establish relationships at the school level, meaning that teachers and RWL coordinators connect with the local business community to forge relationships and set expectations. That said, we do see opportunities for entrepreneurial experiences that can reach across the country or even globally. However, even when business partners are nearby, students connect with them via email, virtually, in person at the school or business. So, it’s a mix of virtual and in-person interactions, but at the core, it’s about building relationships between students and the business community.

What lessons can you share about systems change with others who are working in regions across the country intent on improving educational experiences and outcomes for all students?

Systemic change requires a deep understanding of the system itself. We often talk about change, but rarely do we ask, “What system are we really trying to change, and what are its unique characteristics?” Public education, of course, is the quintessential system—full of unique features that make it quite resistant to change. By working towards every student in Kansas City graduating high school with an MVA, we’re attempting to undo decades of systemized structures that were designed to self-sustain.

Our work is focused on looking for opportunities to replace certain elements and to push on certain levers—whether that be creating school-leader professional development programs to support buy-in or removing barriers to access by forging smart partnerships— but our intention is not to scrap the whole system. Scrapping everything would be a catastrophic failure. Instead, I would invite others invested in similar work to capitalize on what is working, while exploring new opportunities and scaling at the edges. To create lasting systems change, you need to put levers in place until the change becomes commonplace. And remember, it doesn’t happen overnight.

August 29, 2024

This is just a preview of what’s included in our August newsletter, featuring an opening letter from our president, Timothy Knowles. Click below to explore all the updates! Dear Friends and Colleagues, If you look closely at the landscape of secondary schooling across the nation, you will see a sea…

September 26, 2024

This is just a preview of what’s included in our September newsletter, featuring an opening letter from our president, Timothy Knowles. Click below to explore all the updates! Dear Friends and Colleagues, Across the nation, in districts large and small, extraordinary work is taking place to ensure learning is increasingly…