In these Tim Talks, Carnegie President Tim Knowles engages “friends, allies, and conspirators” in micro-conversations about education, equity, and the future of learning.

Our top priority as a country has to be to narrow and ultimately eliminate those large racial gaps that exist in American society in order for us to really share in the prosperity that comes from a more talented society.

Since 2008, Jamie Merisotis has served as the President of the Lumina Foundation, a philanthropic institution that addresses issue of equity across the post-secondary sector through policy, practice, and scholarship. Leader, innovator, and author, his latest book, Human Work in the Age of Smart Machines, provides a roadmap for the large-scale, radical changes needed in order to erase a centuries-long system of inequality so that all can find abundant and meaningful work in the 21st century.

“What is education for?” poses Jamie in his talk with Tim Knowles. “My partial answer … is that it prepares people for the work that only humans can do in an increasingly technology-mediated world. Because for us as humans, work matters.”

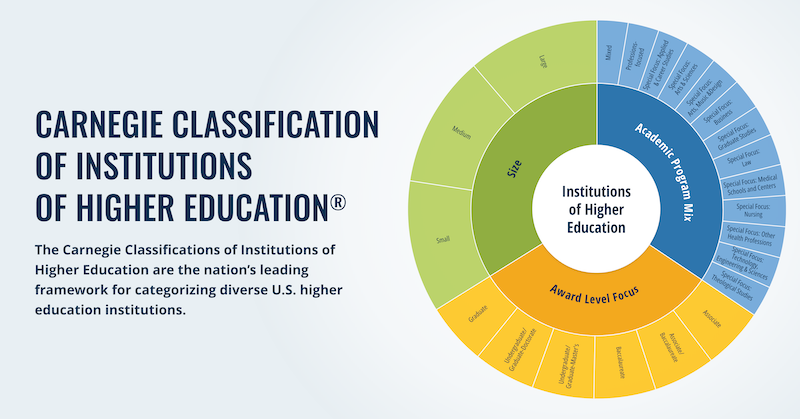

Jamie discusses with Tim the idea of a post-secondary education “ladder of opportunity” in which short-term credentials and associate degrees are not terminal endpoints but onramps to a baccalaureate degree. In this new model, training—where people learn technical work in the fastest way possible—and education—which provides broader learning without a focus on work—are integrated with the understanding that both of these types of learning are needed throughout a life.

“People need to be prepared,” says Jaime, “so we need to rethink how we (educate) because our learning system is no longer sufficient if we treat it as a one-and-done process. We’ve got to treat post-secondary learning as a lifetime set of tasks.”

The post-secondary sector also must be remade to redress its role in narrowing economic and social mobility. “We’ve got to do a better job of putting equity front and center in the system,” says Jaime.” So, I would start there in terms of what are the exciting models or breakthroughs … whatever it may be to try to put the thumb on the scale of equity.”

Transcript

Tim Knowles (TK): Welcome, Jamie. I’m very pleased that you’re joining me today. For those of you who don’t know, Jamie is the president of the Lumina Foundation. And as you should know, Lumina is one of the most important forward-thinking philanthropic institutions in the nation, having impact on policy, practice, and scholarship across the post-secondary sector. Jamie, thank you very much for joining for this micro-conversation about equity and the future of learning. It’s micro only in the sense that it will be brief. I wanted to start by asking you to say something about Lumina priorities and why the Foundation puts the stake in the ground where it has.

Jamie Merisotis (JM): Yeah, thanks Tim and wonderful to be with you, and really happy to have this conversation. You know, it’s interesting, philanthropy’s got lots of different models. When I came to Lumina in 2008, Lumina was doing really, really good work on post-high school learning, on college access and success. When I came, I said, “Look, I think that we’ve got an opportunity here to be a leadership organization, but in order to do that we’ve got to be very specific about what we’re trying to accomplish and to be transparent about it.”

So, we began advocating for this goal that 60% of Americans should have a high-quality degree, certificate, certification, or other credential by 2025, aligned with what at the time was the sort of best in class globally in terms of attainment levels, but also what labor market needs suggested, et cetera. Since we started, 45 of the 50 states have adopted like-minded goals. And what’s interesting about it is that when we started the attainment rate was 38%.

Today, it’s nearly 52%. Now, some of that is because we’ve actually gotten better at counting certificates, but in net terms there are 12 million more Americans who have a post-high school certificate, certification, or degree than when we started. So, that’s good progress. I think that’s an important marker, but at the same time I don’t think we can be complacent about what we know about the demand for talent in our country and how that has to be produced in colleges, in universities, in workforce programs and all the other array of post-secondary learning entities. I think you and I talked recently about this sort of stunning.

I look at the labor market data every month, and back in March where we had a lot of new jobs created there were 916,000 new jobs created in the U.S economy. And and in that same month, only 7,000 went to people who have a high school credential or less. So, it’s pretty clear here that what we need is people with much higher levels of talent and they need to be produced in a formal learning context after high school.

And so that’s what Lumina is all about. We’re about trying to stimulate attainment, increase high-quality credential success, and putting our thumb on the scale of racial equity in all that we’re doing. We believe that all forms of equity are important. Economic equity, social equity, all of the different dimensions, but we believe our top priority as a country has to be to narrow and ultimately eliminate those large racial gaps that exist in American society in order for us to really share in the prosperity that comes from a more talented society.

Our top priority as a country has to be to narrow and ultimately eliminate those large racial gaps that exist in American society in order for us to really share in the prosperity that comes from a more talented society.

(TK): Jamie, that’s actually a great segue. I recently saw a truly stunning piece of research done by the Federal Reserve in Boston and scholars from Dartmouth and The New School, and they were looking at income inequality in a range of American cities. And their findings, in essence the average net worth of white families was $247,000. For Puerto Rican families, the number was $3,200. For Black families, it was $8, and the average net worth of Dominican families in the United States in the particular cities they looked at was $0.

This, it struck me as the most crystalline evidence for why creating social and economic mobility seems like one of the most important aims of post-secondary education. In your view, what are the most important ways to ensure the post-secondary sector accelerates social and economic mobility across the U.S.?

(JM): Yeah, I mean, those are stunning data, Tim and and I think represent, frankly, some of the failings of what we’ve tried to accomplish. There’s a difference, by the way, between income and wealth. Interestingly, we’ve seen the income levels go up modestly for some populations, some non-white populations, but the wealth gap has actually gotten larger, particularly for Black Americans.

And so it suggests that even as we race to try to increase income through high-quality post-secondary learning that issues of racial bias exist and that we need to do a better job of advancing a truly equity and justice-focused agenda if we want to be successful. So, how do we do that as a post-secondary sector?

One of the things you and I spoke about my recent book, Human Work in the Age of Smart Machines, is that we’ve got to do a better job of answering this question, “What is education for?” My partial answer in my book is that it’s to prepare people for the work that only humans can do in an increasingly technology-mediated world, because for us as humans work matters.

But if work matters, that means that what we are looking for as individuals and as a society is work that’s meaningful, that makes a difference, and that contributes to our shared well-being. Post-secondary education has got to grapple with the fact that it has both created opportunities to narrow economic and social mobility and contributed to some of that social and economic mobility all at the same time, because we’ve created an increasing gap between the haves and the have-nots.

So, I think part of what we need to do is actually focus on the fact that we are those engines of social and economic mobility, but we’ve got to keep our eye on how we actually produce graduates that are contributing economically and socially, and where we’re falling short, and how we should be redoubling our efforts to make a difference.

So, for example at Lumina right now we’re very focused on adults, particularly on short-term credentials and associate degrees it’s well aligned with what the sort of post-COVID economic needs are. But it’s also because we think that we’ve got to get people onto these pathways of learning that will take them over the course of a lifetime obviously into our baccalaureate institutions, et cetera, but we’ve actually got to get a lot more people into that system.

But what we’ve tended to do is to say it’s sort of the bachelor’s degree or nothing. And one of the reasons is that we know that the returns to less than baccalaureate education aren’t nearly as high as they are at the baccalaureate level, but let’s be clear: getting people into the post-secondary pipeline is really critical. Then it’s our job as a sector to move people through the pathways.

So, I’m not talking about terminal short-term credentials, I’m talking about a ladder of opportunity that begins with those short-term credentials. And we should be contributing to that as higher education, as a post-secondary sector, even as we try to move more and more people through that system.

The other part of this I think is that we’ve got to do a better job of helping to prepare people not only for what we historically might’ve called the job skills-specific tasks associated with work or the content, but also increasingly the more generalizable things that I think human work will increasingly mandate.

And here’s where the people in the liberal arts are saying, “Ah, this is our time for a resurgence.” It is, because what I think we do need more of is critical thinkers, and problem-solvers, and people who are ethical, and empathetic, and who can collaborate. But we’ve got to deliver that in new and better ways.

This is not about simply pumping money into the old model. It’s about rethinking how we do that, because our learning system is no longer sufficient if we treat it as a one-and-done process. We’ve got to treat post-secondary learning as a lifetime set of tasks. And we in higher education in the post-secondary sector have to contribute to that in terms of how we deliver that learning.

What I think we do need more of is critical thinkers, and problem-solvers, and people who are ethical, and empathetic, and who can collaborate.

(TK): Speaking of pumping money into the system, my penultimate question is maybe the hardest one. It’s a political question about the current administration and to reflect a little bit about what it can do in, in this current climate, which I don’t have to describe, to best support the kinds of innovations and improvements that you’re talking about as requisite.

(JM): So, there’s sort of a good news, bad news situation I think that we’ve got to face. The good news, the overwhelmingly, it’s overwhelmingly good news, let’s start there. Which is that 2021, we’ll probably look back on 2021 and realize that it’s a hundred-year flood of federal money. That’s flowing to states, to post-secondary institutions, to K-12 schools. And so I think that’s sort of obvious already.

The American Recovery Act pumped an incredible amount of money into the system at levels that you or I couldn’t have predicted a couple of years ago, right? Even at the height of the economic crisis of 2008-2010, we’re talking about a fraction of the amount of money that went out to prop up the system in an economic crisis.

This time around there was a lot more money, but the risk here, and this is the bad news, is that we are simply going to pump money into propping up an existing system. We can’t afford to do that this time, because the nature of work is changing rapidly. And so are our broader social and democratic needs as a society, right?

So we recognize that climate change is an existential risk. We recognize that authoritarianism is an existential risk. We’ve got to do a better job in higher education, in post-secondary learning of preparing people for a lifetime of active citizenship, of being effective workers. And that’s going to require us to deliver higher education in different ways. So all of this money from the Biden administration and Congress is going to be good news if we use it to innovate and improve.

If we use it to prop up the existing system, I fear that we will get the same sort of middle-of-the-road, below-average results that we’ve seen for the last few decades and that’s going to put us further and further behind both from an economic perspective, but I think we now recognize increasingly from a social and democratic perspective as a country.

(TK): So, I promised this would be a micro-conversation so one more question, and you just alluded to it. Looking ahead, I’m curious to hear you say it, what’s on your mind in terms of where there is the most promise, and in terms of the most exciting models or breakthroughs that you think are emerging at a time of existential crisis for post-secondary education in general, I think, and conversely, if you would, what the … where the perils are, and you just alluded to a little bit of it, but where the perils are in the sector, particularly in terms of achieving educational equity.

(JM): Yeah. The perils are ever-present and growing. And we saw obviously in COVID that the people most affected by the disease were in fact people of color, women, the frontline workers, the people who were most at risk. And so I think the perils are pretty obvious, which is that we’ve got to do a better job of putting equity front and center in the system.

So, I would start there in terms of what are the exciting models or breakthroughs. It’s the ones that actually do that. And we’re seeing a growing number of states actually prioritize equity in what they’re trying to do. States like Virginia, Colorado, and some others where they’re actually making racial equity an explicit focus of what they’re trying to do using funding models, using incentive programs, whatever it may be to try to put the thumb on the scale of equity. And I think that that’s exciting.

The second, I think, at the sort of institutional level, the higher ed institutional level, is those schools that are actually trying to target learners to give them those pathways of learning, what I call in my Human Work book “wide learning opportunities,” right? Wide in time, wide in content, and wide in who they’re serving. Sort of different than this idea of “deep learning,” which we talk about in the realm of AI and technology.

And so humans are wide learners and the institutions that are approaching learning from a wide perspective, I think, are the ones that are going to be most successful. Interestingly, a lot of those are in community colleges right now. They’re understanding that they’ve got to meet the learners where they are, bring them into and through the system, and help them be more successful over the long-term.

Places like El Paso Community College, which is doing a really good job of serving people on and near the border. I’m working very closely with UTEP as a collaborative partner. Really, really good example of a sort of approach that really is about taking that notion of wide learning into account.

But I think that we are looking in at higher education at a time of both great risk, but also great opportunity. And it’s on us as leaders in the sector to seize the moment here and actually transform higher education in the way that society needs in the same way that we did after World War II, in the same way that we did in the civil rights era, in the same way that we’ve tried to do more recently when it comes to things like LGBTQ+ rights and things like that.

This is our moment, this is our opportunity, but we’ve got to seize it because the risks to American society have never been greater.

This is our moment, this is our opportunity, but we've got to seize it because the risks to American society have never been greater.

(TK): I couldn’t agree more, Jamie, that the opportunity is really palpable now and, speaking from the perspective of the Carnegie Foundation, think that the opportunity for new models for real breakthroughs, as you suggest, in terms of meeting young people and not-so-young people where they are, and actually figuring out the pathways and pipelines to legitimate, wealth-generating, family-sustaining lives is here. And so it’s exciting to hear you be hopeful about that as well. Really appreciate your leadership, really appreciate Lumina’s leadership, and thank you for taking a few minutes to chat.

(JM): Thank you, Tim, and thank you for your leadership. Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching is just an incredibly important leader, both in the K-12 and higher ed realms. We’re going to need more of you going forward.

(TK): Well, we better multiply, then. Thanks, Jamie. Appreciate it. Good to talk. All right.

September 7, 2021

Christopher Emdin and Timothy Knowles share a microconversation about the impact of poverty on the imagination, the role of “freestyleability” and “ratchetdemics” in the classroom, and how teachers are performance artists and students their works of art.

November 17, 2021

Tim Knowles talks with Carnegie board chair Lillian Lowery about the importance of teachers of color, the changing role of assessment, and the future of the classroom.