In my previous post, I took on the question, “Under what conditions is the idea of fidelity of implementation the appropriate conceptual organizer and when may it be less so?” Though measuring “fidelity of implementation” is increasingly used as a moderator for variation in effects across sites, the programs under study are complex and take place in different contexts. I argued and illustrated how an alternative concept—adaptive integration—aligns better with the nature of most educational interventions and the contextual changes they often entail.

This same set of issues also arise in the search for “bright spots.” These studies tend to focus on identifying specific work practices, tools, and other materials that are thought to contribute to unusually positive results found in some classrooms, schools, or districts. Such inquiries may well identify the what of improvement, but under attend to how these positive results actually came to be.

Many interventions, even ones that may appear “simple,” require sustained, cooperative, collective action among organizational participants.

The latter includes considerations such as: additional work time that may be needed to implement the intervention (surprisingly, this often is not factored into programmatic thinking); the amount of individual and organizational learning that may be required to engage the intervention effectively; and the base quality of social relationships operative in the organization.

Many interventions, even ones that may appear “simple,” require sustained, cooperative, collective action among organizational participants. These interventions may ask individuals to take risks in trying out new work processes and to engage in difficult conversations with one another to advance change. They may also make demands on shared moral resources (i.e., we collectively believe this is the right thing to do).

The search for bright spots needs to focus on both “what” seems to be producing the positive outcomes observed and also “how” an organization came to work so effectively in this fashion.

In such situations, relational trust becomes essential for effective local take-up and use of the new intervention. To the point, Barbara Schneider and I documented in our book, Trust in Schools, how relational trust among principals, teachers, parents, and community leaders played a very strong role in differentiating effectiveness among local school efforts for advancing educational improvement. To describe this phenomenon, Barbara and I introduce the analogy of a sieve. Schools with weak relational trust are like a sieve with huge holes. No matter how well-formed the intervention (think of a viscous sauce), it just flows right through. Nothing gets picked and used well. In contrast, when relational trust is strong, the holes in the sieve are miniscule. In such a place, many different interventions can potentially be made to work.

In short, the search for bright spots needs to focus on both what seems to be producing the positive outcomes observed and also how an organization came to work so effectively in this fashion. Absent the latter, I fear that we will continue to search for promising practices that do not productively scale.

March 17, 2016

Studies on the effects of educational programs often focus on “fidelity of implementation.” But this approach often fails to consider the complexity both of the programs themselves and of the demands they place on the contexts in which they are carried out.

April 6, 2016

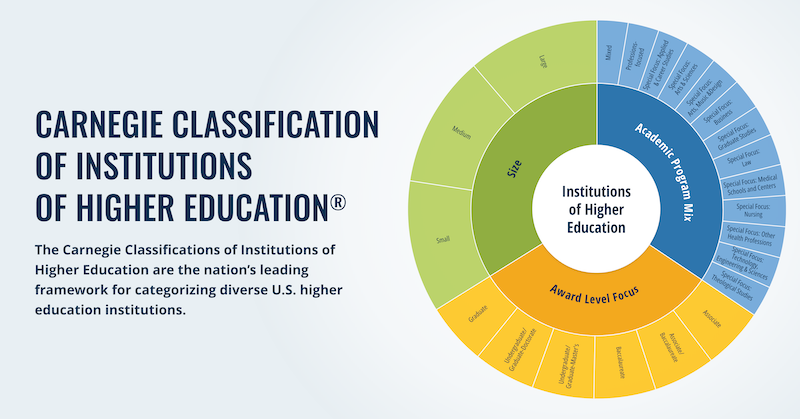

Carnegie Foundation President Anthony Bryk recounts his experience of facilitating a workshop activity that enabled participants to accelerate their collective problem-solving and helped them see the power of attacking a common problem as a structured network.